Most Young People, Especially Creatives, Can’t Afford to Live in Big Cities

Most Young People, Especially Creatives, Can’t Afford to Live in Big Cities

Between the ages of 22 and 33, I rented 5 different apartments, all in different neighbourhoods, in Toronto. After 6 years working in television, I was able to afford a one-bedroom condo with my wife. We eventually sold that and bought a fixer-upper house in the city’s east end in Leslieville. Even though we both had good jobs, eventually we left the city, like so many others, because our mortgage, and the cost of living was more than we were earning. I can’t help but think how hard it must be for young people to get started in a city like Toronto now. There is no question it has become more expensive for young people to live in big cities.

In the early 2000s, after my shift at CityTv, I would go to practice with my indie rock band at our rented rehearsal studio. My drummer had an apartment in Liberty Village, not far from where we rehearsed at Bathurst and Queen Street. I can remember his neighbourhood starting to transform in the early 2000s. In that stretch of Queen St. and King St. West, there was an interesting mix of small art studios, apartments, restaurants and music venues. During those years, Liberty Village went through a huge gentrification process. Now, primarily populated by new and expensive condos, mostly rented by younger people, and owned by investors and wealthy people, many of the artists, studios, and shops are gone. I remember we used to play gigs at The Reverb, on the corner of Bathurst and Queen Street. Unfortunately that venue and many more in Toronto’s west end neighbourhoods have closed down. Now, it’s even hard to find a rental music rehearsal space in the downtown core.

I left Toronto in 2015, so it has been a while since I lived there, but I have heard many of the indie music venues have closed down because rental prices climbed too high. Although some of the recent challenges in the arts scene are the result of COVID-related economic problems, since the pandemic ended, live music venues continue to struggle to make ends meet. At the same time, I repeatedly read articles about extremely high rental costs in Toronto, and the lack of affordable housing for first-time buyers. The creative city craze that happened in the late 90s and early 2000s in Toronto seemed cool at the time, but now I can see it was superficial, and it killed a lot of great arts scenes in the city.

I remember hearing about Richard Florida’s book, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, a lot when I worked for Bravo Arts Television; we did at least two or three feature stories on him. Working for an arts television program, a lot of the gallery and exhibition events we covered had a cosmopolitan and global tourism type of focus. Many of those in government and in cultural planning sought to attract global tourists and tech workers by advertising bohemian and creative city neighbourhoods for them to visit, live, and work in. These activities were seen as good economic drivers for urban development. Although it all seemed exciting at the time, I didn’t realize the “creative city” movement would end up marginalizing young creative people and contribute to an ongoing exodus where they are leaving Toronto’s downtown neighbourhoods.

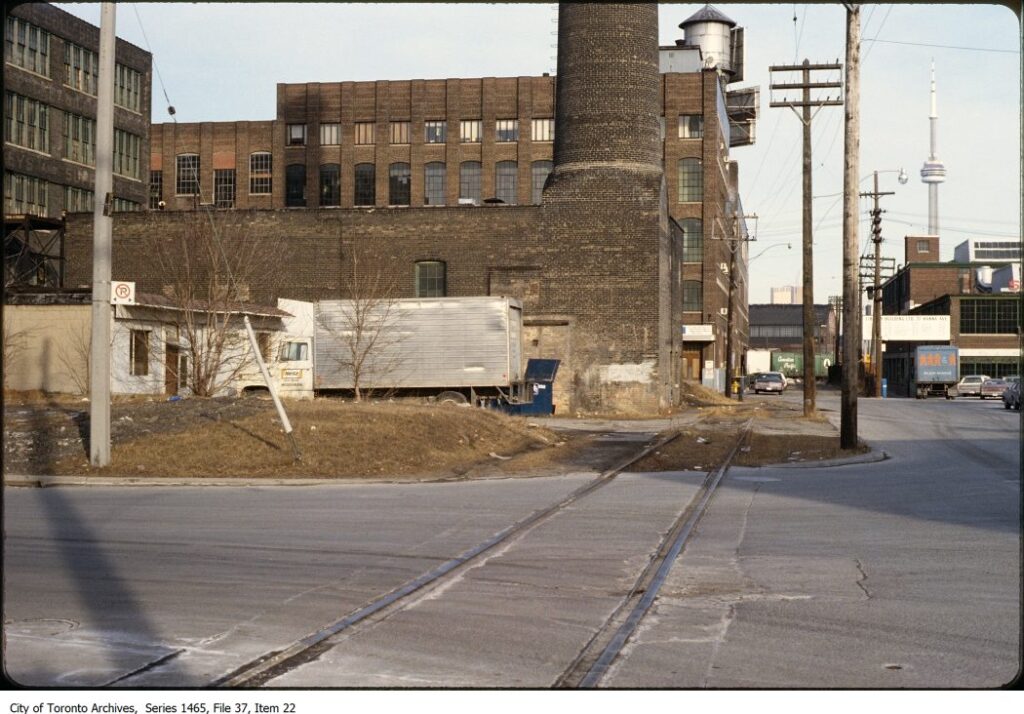

Liberty Village in the 1970s

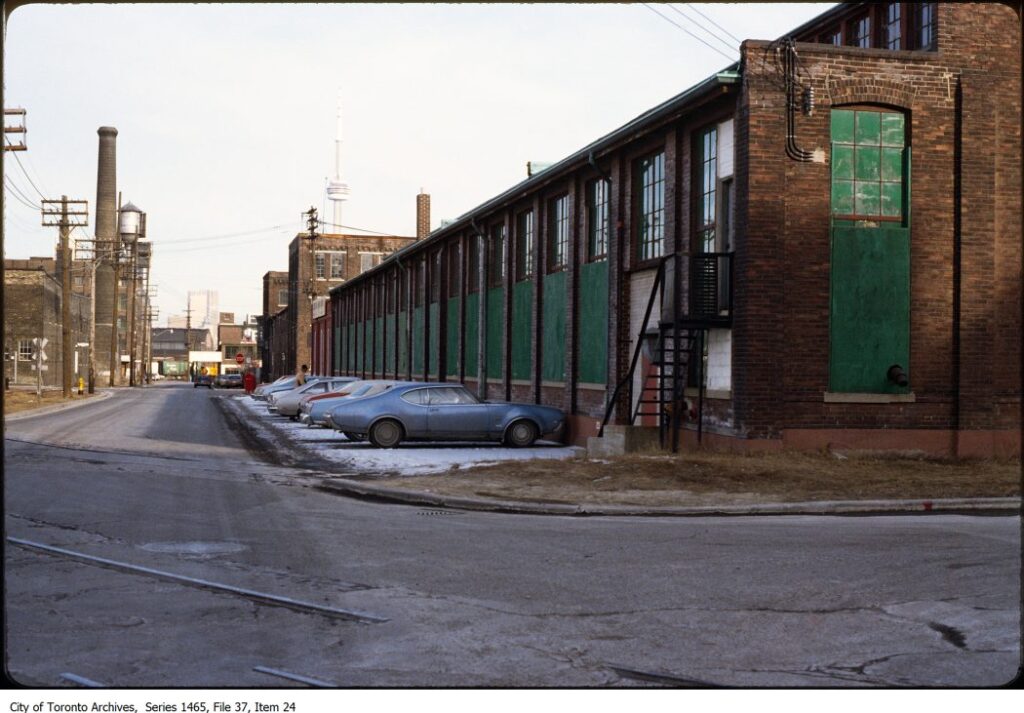

Liberty Village in the early 1990s

Courtesy of Alex Luyckx

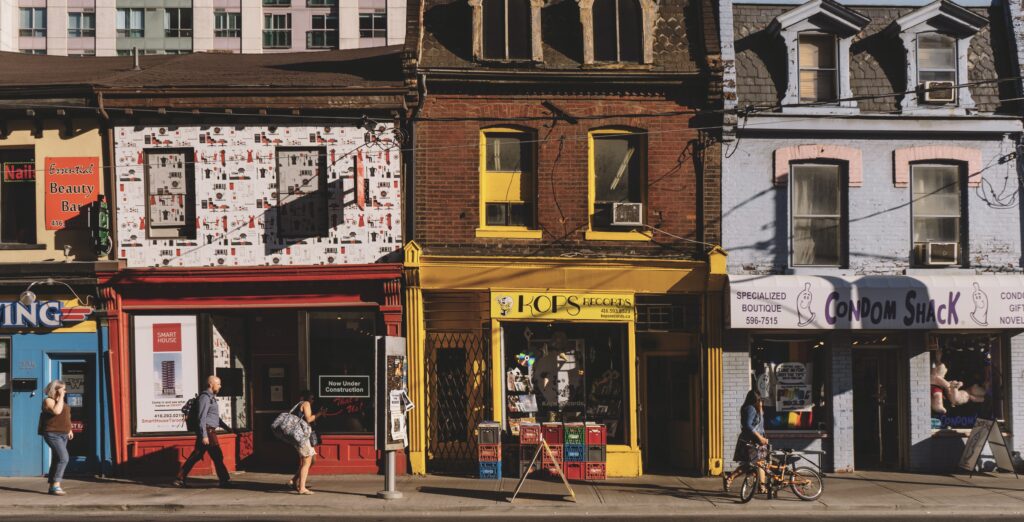

Liberty Village 2020

Ideas about cultural industries and creative commercialization have been discussed since the emergence of modern cities in the 19th century. In the post-Fordist economy, there was a new focus on specialized markets rather than factory-driven mass production. City planners began to see culture as a new important economic driver (O’Connor et al, 2020). In the 1970s UNESCO and the Council of Europe began researching cultural industry development in cities. In the early 1980s, the Greater London Council focused attention on cultural industries as an important part of economic development. At the start of the 21st century, with many economies focussing on innovation, and with the addition of the internet and digitization, creativity was seen as important element for building strong economies (Moore, 2014).

Following the publishing of the best seller, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life by Richard Florida in 2002, Toronto and other cities championed the idea of the “creative city.” Florida suggested developers should not invest in large public event-type facilities (stadiums) or provide corporate tax breaks to build the urban economy, rather they should build communities with vibrant arts scenes that attract young hipsters and tech professionals (Florida, 2002). Many cities around the world, Toronto included, embraced Florida’s ideas as they looked for new ways to attract a global cosmopolitan audience to their neighbourhoods. In the early 2000s, a flurry of cultural development and city rebranding fuelled massive real estate and gentrification projects in large cities around the world (O’Connor et al, 2020). However, in 2023 many see that the creative city dream has not delivered the kinds of neighbourhoods and economies its proponents promised.

Unfortunately for many cities, the creative city experiment has turned out to be yet another exercise in gentrification. Twenty years down the line, since the publishing of Florida’s best-seller, there seem to be even larger gaps in wealth, opportunity, and accessibility in large urban centres. Urban development based on the creative city concept marginalizes groups of people in three related ways: (1) it pushes residents and artists out of flourishing neighbourhoods, (2) the benefits favour small groups of politicians, real estate investors, and creative professionals, and (3) it exacerbates the problem of socio-economic polarization in large cities.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Liberty Village in Toronto’s west end was a flourishing neighbourhood inhabited by a mix of artists and working-class people. The area saw intensive gentrification, to the point where condos now tower over the area, working-class residents have been alienated, and many people have been priced out of the neighbourhood, even the artists that attracted the development in the first place (Catungal et al, 2008). The funky bohemian neighbourhood was pitched as a desirable place for working professionals to live. Twenty years later, now that many of the original residents and local artists have moved away from the area, it’s hard not to think the only beneficiaries from this gentrification are real estate developers and wealthy investors.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, city planners and developers rebranded city neighbourhoods, not only to attract young tech professionals to the area but also to attract tourists. Planners and developers convinced locals that development would be good for everyone, when really the main goal was to attract enterprise and high-tech industry. Urban planners moved into bohemian neighbourhoods and recreated the atmosphere, setting up museums and events designed to attract a global audience to the city. The connection to the neighbourhood is misunderstood by wealthy developers and investors, whereas the local residents have a deeper direct connection to the space because they live and work there. This type of gentrification marginalizes the cultural diversity that is used to tout the attractiveness of the neighbourhood in the first place (Philo & Kearns, 1993).

The popularity of the creative city concept in the early 2000s is just another iteration of the pre-existing process of urban gentrification. Smith (1996, as cited in Kirchberg & Kagan, 2013) sees gentrification as the social agenda of restructuring the economy, usually at the expense of the working class, and also usually displacing lower-income people. Kirchberg & Kagan (2013) describe gentrification as a four-phase process: 1)bohemians are drawn to a funky cheap neighbourhood, (2) art galleries begin to pop up and the media begin to promote the area in a positive light, (3) trendy ground-level shops appear and rent prices start to rise, (4) condo development accelerates, rent goes up, wealthier tenants move in, artisans move out of the area, and generic or commercial art galleries dominate the area. The irony is, these neighbourhoods that the city has touted as being unique are now generic and have an element of “sameness”, not diversity (Pratt, 2011, p. 123). Wealthy investors and developers have trivialized the culture by ignoring the individual, historical, and contextual experiences of the local residents. In many ways, the imperfections and grittiness of these artistic neighbourhoods is what attracts people (Philo & Kearns, 1993).

After gentrification takes place in the creative city, the “undesirable” residents are displaced to other neighbourhoods they can afford, and the artists, who were used to sell the area have also been priced out. Security and improved street lighting surrounding these newly developed areas often illustrates the presence of the new affluent ownership. This type of presence and geographic delineation is a signal to adjacent lower-income neighbourhood residents to stay out (Catungal et al, 2008).

Wealthy investors and developers do not have the same connection to the neighbourhood as the local residents and artists. These areas are seen as evolutionary creative neighbourhoods with a dynamic interaction between the artists and the place. As elder tenants and low-income residents are evicted from the neighbourhood, developers demolish spaces that don’t relate to the lifestyles of the affluent or upper class. These places are then recreated to suit the needs and images of an “authentic neighbourhood” as seen by the wealthy (Kirchberg & Kagan, 2013, p. 138).

And so it becomes clear that gentrification under the guise of the creative city concept pushes residents and artists out of flourishing neighbourhoods. Gentrification benefits a small group of people at the expense of everyone else. So what is to be said of the artists and creative workers in the creative city after gentrification has happened? It is important to distinguish creative professionals who work in tech and media industries from lower-income creative workers and artists. In many of these gentrified neighbourhoods, the only artists that remain are higher-paid creative people working in tech or media.

In 2023, it seems clear to many people that the promises of creative cities and creative labour have ended up benefiting real estate developers and investors (O’Connor et al, 2020). Although some of the beneficiaries are indeed creative workers, it is only a small section of what could be considered creative or artistic workers. Creative city developers often reference artists as the driving force behind economic growth, but they often refer to creative professionals working in the software and computing industries (Banks & O’Connor, 2017). Pratt (2011) argues that the vagueness of such championed ideas focuses on the “quality of life of the few.” Gentrified creative city neighbourhoods attract “senior or middle management and cosmopolitan migrants.” Although these practices are often promoted as being progressive, they are regressive (p. 125).

As with most urban development projects, the benefits are in the interest of politicians, corporate leaders, investors, insurance professionals, and real estate people (Kirchberg & Kagan, 2013). In much of the discourse surrounding creative city concepts, there is a lack of distinction made between types of creative workers and artists. It seems that the word creative is being used in multiple ways: 1) it’s being used to describe all artists, creative workers, or bohemians as the foundation for creating culturally diverse and interesting neighbourhoods, and (2) creative city discourse often makes references to creative workers as specifically upper-middle-class workers in tech, software, and computing.

Urban development based on creative city concepts neglects to consider the diverse circumstances that created the neighbourhood in the first place. These diverse circumstances include creative and working-class people of all types. Creative city developers focus on a specific category of artists, which is part of a top-down approach. To build a real creative culture, there needs to be an environment that fosters the complex interplay of many types of labour and production. If the neighbourhood lacks diverse ways to earn a living it will lack a ground-up bohemian arts scene, and many of the higher-paid creative tech people will not be attracted to the area (Scott, 2006). Scott (2006) explains that “creativity is not something that can be simply imported into the city on the backs of peripatetic computer hackers, skateboarders, gays, and assorted bohemians, but must be organically developed through the complex interweaving of relations of production, work, and social life in specific urban contexts” (p. 15).

Although investors, politicians, and real estate developers often promote creative cities as being good for everybody, ideas of community inclusion are often biased and narrow. Alsayel et al (2022) suggest developers seem to “cherry-pick” what aspects of inclusion they wish to adopt. The authors assert that whenever there is a conflict between inclusion and creativity, creativity tied to economic needs and interests will always prevail over inclusion (p. 10). Ultimately, this type of progressive development marginalizes large segments of the population in a developing neighbourhood. These types of exclusionary developments have also led to rifts within communities of artists and creative workers. The displacement of the working class, manufacturing workers, and artists such as craftsmen, photographers, and organizers, suggests that creative city development is exclusive (Catungal et al, 2008).

In many ways, creative city development has a polarizing effect because it tends to benefit a small group of people while excluding large numbers of the population. “These same flows have undermined public services – free education, public health, affordable housing – in such a way as to increasingly exclude younger middle-class people from the modern future on which their aspirations so relied” (Davies, 2020 as cited in O’Connor et al, 2020, p. 5). After twenty years of creative city development, in cities like Toronto, economic polarization has meant living in downtown neighbourhoods is unattainable for much of the workforce, let alone creative workers. A small percentage of people continue to acquire wealth through property ownership in these areas, while an increasing number of professionals can only afford to rent, or must commute from further out neighbourhoods (Statistics Canada, 2022c). So, instead of creating a diverse and healthy economic environment, development in major Canadian urban centres continues to marginalize large sections of the population, creating polarized and less culturally and economically diverse neighbourhoods.

Polarization of Wealth and Property in Urban Centers

In the big Canadian cities, there is an ongoing exodus from the downtown cores. From 2019 to 2020 Toronto and Montreal saw a record decrease in population, primarily as a result of people moving from the downtown area to the suburbs (Statistics Canada, 2020). From 2016 to 2021, population growth in the peripheral municipalities was greater (6.9%) than in the central municipalities (5.5%) (Statistics Canada, 2022a). Part of the problem, at least for creative workers, is there tends to be more work opportunities in large urban centres. Although creative and cultural work generally pays low anywhere, this type of work is harder to find outside of urban centres, and it pays even less in smaller communities (Banks & O’Connor, 2017). This is not to say that the creative class is the only group of people leaving urban centres. Unfortunately, the trend is affecting people from all sectors of society, in particular young working people.

In major Canadian urban centres, the polarization and imbalance of wealth continues. There has been an increase in the number of renters and a decrease in the number of property owners. Also, there has been an increase in the number of multiple property owners. From 2019 to 2020, multiple property owners owned 31% of residential properties in Ontario. In Canada, multiple property owners owned one third of all residential properties, and the top ten wealthiest owners owned one quarter of all residential dwellings. Since 2011, the growth in rentals has more than double the growth of home ownership. Over one third of dwellings built in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver from 2016 to 2021 were condos (Statistics Canada, 2022c). Although there are likely other factors leading to the migration of populations from urban centres to peripheral municipalities, urban development and gentrification based on creative city concepts have contributed to the polarization of wealth and property ownership.

There is a sort of an “ongoing buy-out from the promise of the creative city, at least amongst the young who are very aware of its failed promises.” Living in a creative urban centre, for many, seems out of reach as the “disenchanted young creative class” are aware the “creative city serves the few.” Also, it is important to acknowledge that the dream of the creative city is seen as a western thing by many people around the world whose countries and economies simply have no chance of achieving this ideal (O’Connor et al, 2020, p. 5).

Pratt (2011) suggests creative city concepts have created consumption hubs which are not sustainable and that we need a better understanding of the relationship between creative production and consumption (p. 125). According to Kirchberg & Kagan (2013), the exchange of value, not the consumption of value, should be the driving force behind creative urban development. Focussing on consumption, and not the exchange of value, leads to a polarization where there are too many consumers and not enough producers and exchangers. Scott (2006) says we need to find a way for all types of creative people to continue to live and work in these neighbourhoods. We need to foster the diverse circumstances that create interesting neighbourhoods in the first place. Economic and cultural policies need to be pursued at the same time (p. 9-11). We need to “move beyond the tourism, heritage, and consumption focus of many initiatives and embrace the full cycle of culture-making that includes cultural production” (Pratt, 2011, p. 129).

In Canada, with property prices continuously rising in urban centres, and a concentration of home ownership in the hands of the few, creative city developments have exacerbated the problem of socio-economic polarization. Building a vibrant creative city can’t just be about creativity and innovation. It must also be about inclusiveness and acknowledging the other working sectors that support and make up the vibrancy of neighbourhoods (Wainwright, 2017). This sort of top-down approach ignores the complex interplay between all types of production and consumption that contribute to the culture of a neighbourhood (Scott, 2006). Local residents understand the imperfections and grittiness of their bohemian neighbourhoods, whereas investors and developers simplify and trivialize these important factors (Philo & Kearns, 1993). Art and creativity should not be seen simply as a sector, rather they should be integrated into all parts of society. Creativity, art, and design should be seen as integral elements that can be catalysts for many purposes, in many parts of society and work. Building creative and inclusive neighbourhoods should be a bottom-up approach where “long-term developments and processes are regarded as important, rather than products” (Kirchberg & Kagan, 2013, p. 141).

References

Alsayel, A., de Jong, M., & Fransen, J. (2022). Can Creative Cities Be Inclusive Too? How Do Dubai, Amsterdam and Toronto Navigate the Tensions Between Creativity and Inclusiveness in Their Adoption of City Brands and Policy Initiatives? Cities, 128. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103786

Banks, M., & O’Connor, J. (2017). Inside the Whale (and how to get out of there): Moving on From Two Decades of Creative Industries Research. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(6), 637–654. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549417733002

Catungal, J. P., Leslie, D., & Hii, Y. (2009). Geographies of Displacement in the Creative City: The Case of Liberty Village, Toronto. Urban Studies, 46(5–6), 1095–1114. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009103856

Davies, W. (2020). Bloody Furious. London Review of Books (Vol. 42, p. 4).

Florida R. L. (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. Basic Books.

Florida R. L. (2005) Cities and the Creative Class, New York-London, Routledge

Florida, R. L. (2017). The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class– And What We Can Do About It. New York, Basic Books.

Garnham, N. (2001). From Cultural to Creative Industries: An analysis of the Implications of the “Creative Industries” Approach to Arts and Media Policy Making in the United Kingdom. Retrieved from. http://nknu.pbworks.com/f/FROM%20CULTURAL%20TO%20CREATIVE%20Industries.pdf

Kearns G. & Philo C. (1993). Selling Places: The City s Cultural Capital Past and Present (1st ed.). Pergamon Press.

Kirchberg, V., & Kagan, S. (2013). The Roles of Artists in the Emergence of Creative Sustainable Cities: Theoretical Clues and Empirical Illustrations. City, Culture and Society, 4(3), 137–152. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2013.04.001

Moore, Ieva (2014). Cultural and Creative Industries Concept: A Historical Perspective. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 110: 738–746. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042813055584?via%3Dihub

O’Connor, J., Gu, X., & Kho Lim, M. (2020). Creative Cities, Creative Classes and the Global Modern. City, Culture and Society, 21, 100344. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2020.100344

Pratt, A.C. (2011). The Cultural Contradictions of the Creative City. City, Culture and Society, 2(3), pp. 123-130.

Scott, A.J. (2006) Creative Cities: Conceptual Issues and Policy Questions. Journal of Urban Affairs, 28, 1-17.

Statistics Canada. (2020). Canada’s Population Estimates: Sub-Provincial Areas, July 1, 2020 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/210114/dq210114a-eng.pdf?st=UEtN5wqf

Statistics Canada. (2022a). Canada’s Fastest Growing and Decreasing Municipalities From 2016 to 2021. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-x/2021001/98-200-x2021001-eng.pdf

Statistics Canada. (2022b). Canadian Housing Statistics Program, 2019 and 2020.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/220412/dq220412a-eng.pdf?st=BJVJ4b60

Statistics Canada. (2022c). To Buy or To Rent: The Housing Market Continues to be Reshaped by Several Factors as Canadians Search for an Affordable Place to Call Home. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921b-eng.pdf?st=XbGx4RIs

Taylor, C. (2015). Between Culture, Policy and Industry: Modalities of Intermediation in the Creative Economy. Regional Studies, 49(3), 362–373. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748981

Wainwright, O. (2017, October 26). Everything is Gentrification Now: but Richard Florida Isn’t Sorry. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/oct/26/gentrification-richard-florida-interview-creative-class-new-urban-crisis